Yama Farms Inn: A Home in the Mountains

Yama Farms Declared an Historic Landmark

Following the sale of the Inn in 1944, the structures and grounds that comprised Yama Farms gradually deteriorated. A number of the structures were intentionally destroyed, others fell to ruin due to neglect. The surviving structures faced an uncertain future. Beginning in the summer of 2010, several “friends of Yama Farms” began gathering information about the property’s condition and finally brought the matter to the attention of the newly-created Town of Wawarsing Historic Preservation Commission. The latter was authorized in 2005 and fully activated in 2010 with the appointment of five Commissioners, who meet once a month with a mandate to protect the historical legacy of the Town. Upon review, the Commission concluded that eight Yama Farms structures should be given Local Landmark status “because of their unique architecture, their important role in the history of our region and the United States, and their connection with many famous people.” On May 19, 2011, in response to the Commission’s recommendation, the Town of Wawarsing conferred landmark status on the structures. Under the Town’s Historic Preservation Code, the exterior appearance of these structures can no longer be altered without the Commission’s approval.

Descriptions and images of the landmarked structures appear below.

The Hut

The Chalet

The Hut and the Chalet:

The Hut, constructed circa 1906-1910 as part of Yama-no-uchi, was the private home of Frank Seaman and Olive Sarre as well as the location where they received many of Yama Farms’ most famous guests. The Hut is a low but impressive log structure. While not as overtly Japanese as the other Yama-no-uchi structures, the Hut’s design reflects Japanese ideas of simplicity. Until the recent disappearance of its gently sloping gable roof, it represented a major example of the Arts and Crafts approach to architecture, a style of architecture advocated by Yama Farms’ guest Gustav Stickley. However, a number of Arts and Crafts elements can still be seen at the Hut. Among the more visible is the naturalistic piling up of stone at the exterior base of the northernmost chimney.

Contained within the Hut’s walls are important artifacts and architectural details, which as a group serve as important material reminders of Yama Farms’ aesthetic and historic significance. Among these are two inscribed fireplace mantles. A beautifully executed reproduction of the well-known Pompeian Cave Canum mosaic lies at the Hut’s doorway. On the exterior wall nearby are the Yama Farms hat pegs with their brass labels bearing the names of many famous guests.

The Chalet, most likely also constructed circa 1906-1910, is a stone building adjoining the Hut that may have functioned as servants’ quarters. It is still in use as a residence.

The Upper Gatehouse:

This building, constructed circa 1912-1913, stands at the former upper entrance to Yama Farms Inn and was probably built in conjunction with the latter. It has both shingled and cobblestone exterior walls. Its best known historic use was as a restaurant (“The Grill” also known as “The Lodge”) established by Seaman and Sarre to serve the Inn’s “transient guests,” i.e. day visitors. Until damaged by a recent fire, it served as an apartment building.

Views of the Yama Apartments (formerly Offices and Staff Quarters).

Yama Apartments (formerly Offices and Staff Quarters):

This structure was probably constructed circa 1906-1910 as part of Yama-no-uchi. It functioned as a private residence, guesthouse, office space, and staff quarters. There is also a tradition that Seaman and Sarre used portions of the building to breed and raise their prize-winning Black Minorca chickens. During prohibition, wine and champagne were produced and stored in its cellar. More recently, it has served as an apartment building. The exterior walls still retain their original appearance described in Clay Lancaster's The Japanese Influence in America (1963) as “constructed in the Japanese manner … composed of flush horizontal boards held in place by vertical wood strips, protected by deep overhanging eaves.” Other portions of the building’s exterior walls are built of coursed rows of glacial cobbles. The building also features a chimney with a spreading base, mirroring the design of the Hut’s chimney.

The Garage and Staff Quarters:

This building, most likely constructed circa 1912 to 1913, functioned as staff quarters and as an automotive service garage. Much of the ground floor exterior walls are composed of coursed rows of cobblestones. It’s upper story, which includes a series of porches, has shingled exterior walls. This building was most likely the site of the Yama Farms Inn Garage, which is mentioned in a 1919 newspaper advertisement. Double doors on the ground floor open into a large interior space containing one service bay and remnants of automobile repair and maintenance equipment, all appearing to date from the early 20th-century

The Garage and Staff Quarters

Views of the Upper Gatehouse

The Stone Bridge:

Yama Farms’ stone arch bridge mostly likely dates to the Inn’s construction, circa 1912-1913. Spanning the old roadway that leads up the hillside to the Inn, it connected the Inn building with the adjacent nine-hole golf course.

Stone Arch Bridge

The Tea House:

Constructed circa 1906 to 1910 as part of Yama-no-uchi, the former tea house exists today as ruins. Clay Lancaster, author of The Japanese Influence in America (1963), pronounced it “one of the most faithful reproductions of Eastern building forms here.” Its cobblestone podium, with its graceful Asian lines survives, is sited dramatically upon a steeply sloping hilltop. The wooden superstructure has collapsed but some remnants of its original flooring remain intact on the upper surface of the podium. According to a 1913 Travel Magazine, the tea house was built without using a single nail. Artifactual evidence of Japanese carpentry techniques can be found on the ground surrounding the structure.

The Tea House

The Stable:

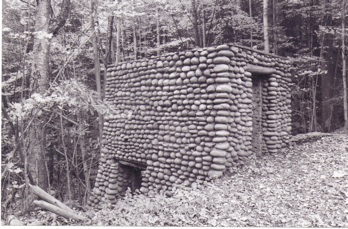

The stable was constructed circa 1906 to 1910 as the centerpiece of Yama-no-uchi. Although it exists today as ruins, the structure retains its Japanese-inspired design qualities. The massive yet graceful walls are composed of coursed rows of rounded glacial cobblestones quarried from the surrounding countryside. Originally these walls formed a podium that supported a wooden superstructure and roof with upturned corners. Clay Lancaster, author of The Japanese Influence in America (1963) likened it to a Japanese castle.

The Stable

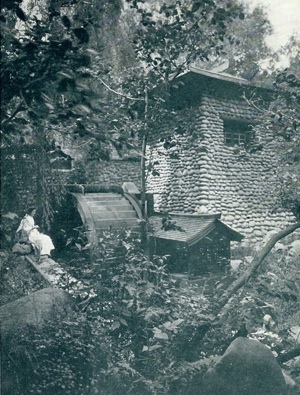

The Turbine Building:

This small structure, mirroring the Japanese-inspired design of the stables and tea house, was built to house a turbine that generated power for Yama-no-uchi. Like several other structures in the Yama-no-uchi complex, all that survives is the cobblestone portion. It also originally contained a pump that distributed water among the trout ponds. Adjoining it were an overshot wheel, raceways, and other hydropower elements. Portions of these also survive.

Views of the that housed the turbine and overshot wheel

Yama Farms and Historic Preservation in the Town of Wawarsing

By Wm. B. Rhoads, Professor Emeritus of Art History, SUNY New Paltz

The Town of Wawarsing has lost more than its share of architecturally and historically important structures. In 1938, after years of neglect, the Johannes G. Hardenbergh stone house, shelter for government records in 1777, collapsed after interior woodwork was extracted for display at H. F. du Pont's Winterthur Museum in Delaware. In 1982 one of the Hudson Valley's finest specimen's of Greek Revival architecture, the Napanoch Reformed Church (1836), was demolished, while the nearby Southwick House, another fine example of the Greek Revival, had been destroyed by fire in 1973. The late 20th century also saw the loss, in the Village of Ellenville, of the Reformed Church parsonage (1872) and the Synagogue (1909) on Center Street.

Now a fire, which has heavily damaged if not destroyed the shingled lodge at the entrance to Yama Farms on Route 55 in Napanoch, has drawn attention to the ongoing deterioration of that once-renowned resort. Created by Frank Seaman and Olive Brown Sarre, Yama Farms hosted leading figures in business (including Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, and Thomas Edison) as well as writers--notably the author-naturalist John Burroughs. The centerpiece of Yama Farms, a low but impressive log structure known as the Hut, was, until the recent disappearance of its gently sloping gable roof, a major example of the Arts and Crafts approach to architecture as advocated by another guest of Seaman and Sarre, Gustav Stickley. Stickley was America's foremost advocate of the Arts and Crafts in architecture and furnishings though his Craftsman magazine, which had a place in the Yama Farms library. Olive Saare, after traveling in Japan with Seaman, served as his "architect" and designed several remarkable Japanese-style structures, including the long-demolished entrance gate and now-ruinous tea house and stables-garage.

Yama Farms was important for its association with notable Americans and for its distinctive architectural design, mingling the sturdy simplicity of the Arts and Crafts movement with the influence of Japan design, the latter unusual but not unknown in early 20th-century America. Its importance was not merely regional but in fact national. Clay Lancaster included a section on Yama Farms in his distinguished book, The Japanese Influence in America (1963). More recently, Harold Harris, Wendy E. Harris and Dianne Wiebe have written a comprehensive history, Yama Farms: A Most Unusual Catskills Resort (2006),

While much has been lost at Yama Farms, there are significant structures remaining, including the ruined cobblestone walls of the stables and tea house, and log walls of the Hut. Even if never restored, these ruins deserve preservation. An active Town Preservation Commission can work to educate the public and especially owners of historic structures about the significance of these structures and the real benefits of preservation for the people of Wawarsing. The Preservation Commission can cooperate with those who for years have struggled valiantly to retain and reuse architecturally and historically significant buildings, such as Ellenville's Hunt Memorial, so that the pace of landmark loss can be slowed if not stopped.